Cultural Heritage

Places that speak to the past and nurture the Park's identity

Share

Browse content

Serra San Bruno (VV)

Charterhouse

The Carthusian Monastery of Serra San Bruno is the first Carthusian monastery in Italy and second of the entire Order, located in a picturesque forest on the outskirts of Serra San Bruno. The walls of the convent stand out solemnly amid the greenhouses, centuries old like the weather of the wilderness.

It is a vast complex founded between 1090 and 1101 by Brunone of Cologne, founder of the Carthusian Order and the Grand Chartreuse near Grenoble, who – scandalized by the corruption of the clergy – had retired to the solitude of the Calabrian woods. Today only a few friars live in the Carthusian monastery, which can be seen every Monday during their walk in the woods. Absolutely forbidden is access to women, as legend has it that if this were the case, the earth would begin to shake. Visits are also not allowed to the impressive Library inside, but only to the Museum, which collects the most significant evidence of art in the Charterhouse.

Stylus (RC)

Cattolica of Stilo

The Cattolica of Stilo is a small religious building located adjacent to the town of Stilo on the slopes of Mount Consolino. The term “Cattolica” probably derives from the Greek “Katholikon,” indicating the place of worship of a monastic complex or the center of cultic reference for hermits who lived in the same area.

Its expressive richness, belonging to a typically Byzantine architectural tradition, places it rightfully among the most remarkable monuments in Calabria.

Mongiana (VV)

Bourbon Ironworks

The Royal Ironworks and Workshops of Mongiana or Mongiana Steel Village or Mongiana Steel Pole was an important iron and steel complex built in Mongiana in 1770 – 1771 by the Bourbon dynasty of Naples. An integral part of the industrial and military complex of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, and a basic plant for the production of ferrous materials and semifinished products (later finished both on site and at the Pietrarsa steel hub), it came to employ about 1,500 workers in 1860. Overwhelmed by events related to the process of political unification of the Italian peninsula, it was put on the back burner by the Savoy government, causing a rapid decline of the steel complex, ending with the cessation of operations in 1881.

Pizzo Calabro (VV)

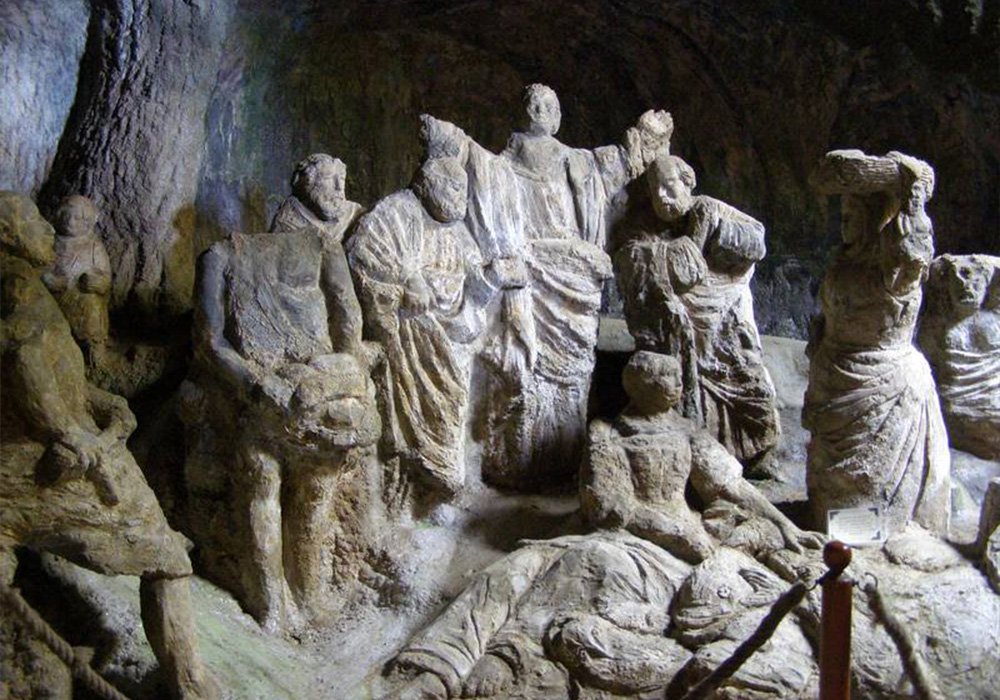

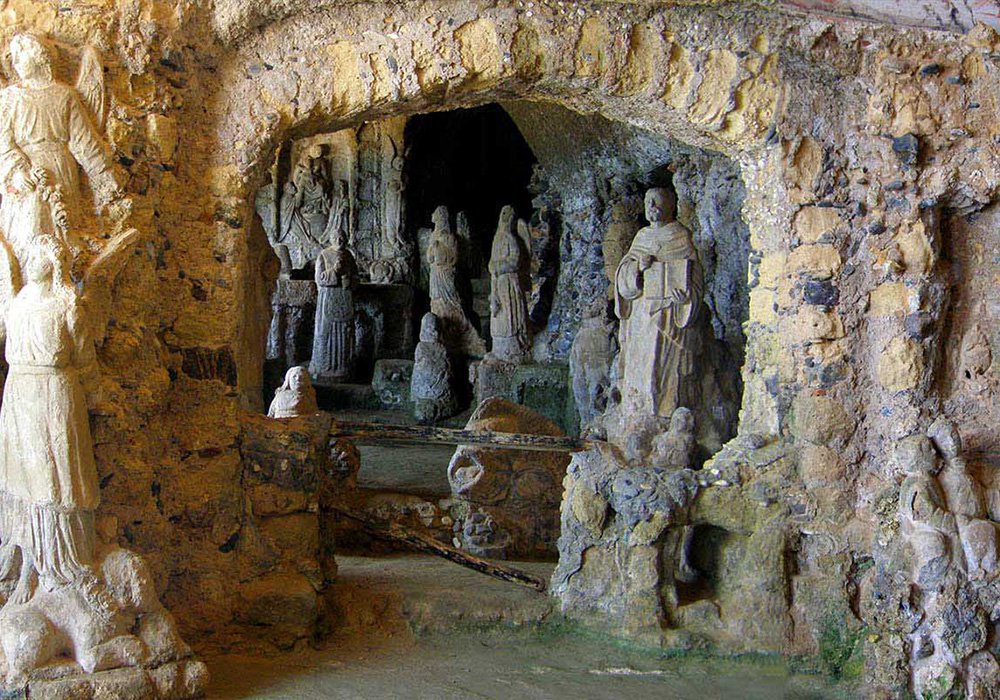

Church of Piedigrotta

A mixture of local history and legend make the Piedigrotta Church unique.

For hundreds of years the legend has been handed down of a shipwreck that occurred around the mid-1700s: a sailing ship with a Neapolitan crew was caught in a violent storm. The sailors gathered in the captain’s cabin where the painting of Our Lady of Piedigrotta was kept and all together began to pray, vowing to the Virgin that, in case of salvation, they would erect a chapel and dedicate it to the Madonna. The ship sank and the sailors swam to the shore. Along with them, the painting of Our Lady of Piedigrotta and the ship’s bell dated 1632 also rested on the shoreline. Determined to keep their promise, they dug a small chapel in the rock and placed the sacred image there. There were other storms and the picture, carried away by the fury of the waves that penetrated all the way into the cave, was always found in the place where the sailing ship had crashed against the rocks.

There are no documents to substantiate this story, but the cult for the image is ancient and much felt by the population, and it would not be far-fetched for the painting to really be the result of a shipwreck.

Bivongi (RC)

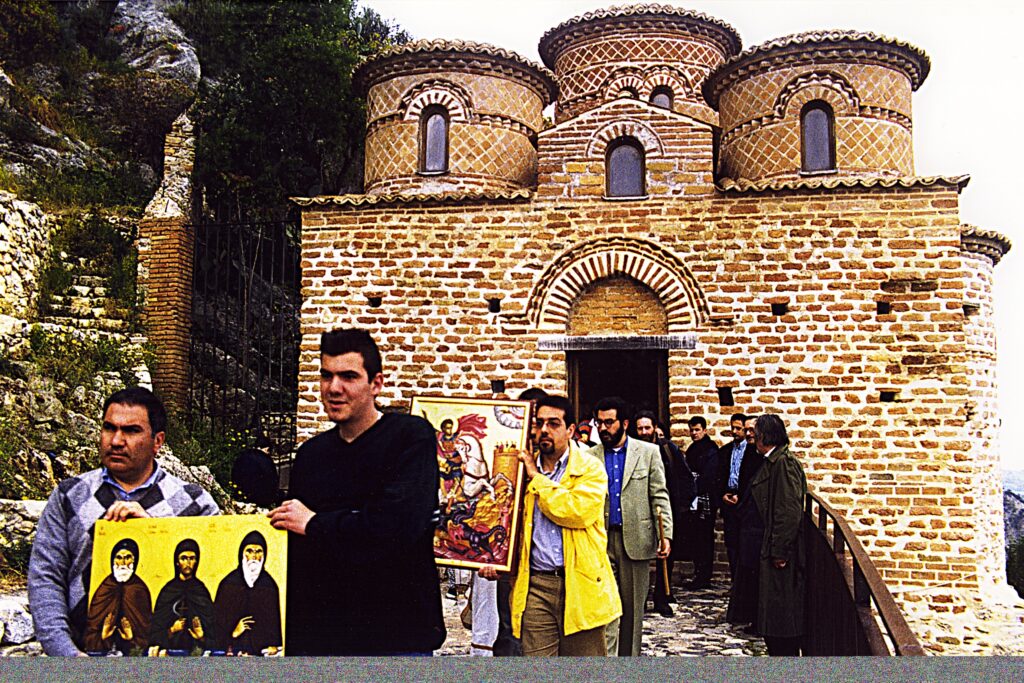

Monastery of St. John Theristis

In the Stilaro Valley lived and worked, in the 9th century, St. John Theristis. After his death, his places and his aghiasma (sacred spring) became a pilgrimage destination, giving rise in the 11th century to a Byzantine Monastery that, in the subsequent Norman period, established itself as one of the most important Basilian monasteries in southern Italy, maintaining splendor and wealth until the 15th century. Its monks were learned and possessed an extensive library. In the 17th century, due to numerous episodes of banditry, the monks decided to abandon the site for good and move to the larger Convent of St. John Theristis Outside the Walls, in Stilo, where the saint’s relics were also moved. In the early 1800s, following Napoleonic laws, the building became the property of the municipality of Bivongi. In 1990 renovations began, and in 1994 the first Athonite monks (from Mount Athos) began to live there permanently. In 2008, the municipality of Bivongi, granted the use of the Monastery to the Romanian Orthodox Church, due to the lack of custody by the Greeks. The Basilica constitutes a clear evidence of fusion between Byzantine and Latin architectural styles: Norman elements can be seen throughout, in the four corner pillars closed by the arches supporting the dome; while, the Byzantine style is evident in the exterior masonry. Traces of frescoes show the depiction of St. John Theristis. The interior is again rich in icons, paintings, frescoes and admirable sacred furnishings, such as the iconostasis and the splendid gold chandelier in the nave.

Arena (VV)

Norman-Swabian Castle of Arena

Arena Castle built in the 11th century by the Normans, occupies a strategic position. Midway between the Ionian Sea and the Tyrrhenian Sea, it represents one of the most original architectural relics of central-southern Calabria.

It was built by Roger in defense of Miletus, in a strategic and impregnable place; it is set on a mighty spur of rock. Roger’s thought was to defend the capital from a sudden attack from behind coming from that eastern coast. To accomplish this important task Roger Conclubet was installed as the first count of Arena, whose descendants would continue to rule in Arena for a good 600 years.

It is because of this castle that the so-called “Castellana of Arena” is held every year. It is a historical re-enactment of the splendor of Arena in the year one thousand that attracts great success and audience participation.

A real leap into the past in which medieval culture is projected among dances, music, flag-wavers, militia, and displays of armaments of the time.

Serra San Bruno (VV)

Shrine of Santa Maria del Bosco

St. Mary’s-a natural cathedral bathed in green and light on fine summer days and soft melancholy in the autumn and winter mists-is the place where St. Bruno built his first monastic settlement, the hermitage of the Tower, in 1091. Visitors will be captivated by the saint’s penitence pond, the so-called “dormitory” (in reality, the cemetery of the first Carthusian hermits) consisting of a cave containing a marble statue of St. Bruno by Stefano Pisani (late 18th century), the church of Santa Maria del Bosco consecrated in 1094 by Archbishop Alcherio of Palermo and today elevated to a shrine. On Pentecost Monday and Tuesday, in memory of the discovery of St. Bruno’s relics in the early 16th century to coincide with that anniversary, the road connecting Santa Maria to the Charterhouse is transformed into a processional space. On Monday the silver bust of the saint is led from the monastery to the church of Santa Maria, in which it remains until the following day when it makes the reverse journey. The Feast of Pentecost also brings to life the Serrese tradition of the Carthusians, little boys and girls who wear the monastic habit of the Carthusians and who, as a sign of devotion or for “grace received,” make the processional route together with their parents. The Monday and Tuesday of Pentecost processions are also the time for another very special local custom, the throwing of confetti with which the faithful strike the reliquary bust of St. Bruno, precisely for this reason protected by an unbreakable dome after no small amount of damage had been done to the precious simulacrum in past centuries as a result of this rite. The fascination that springs from these places is difficult to describe, and perhaps no one has succeeded in rendering it better than the words of the famous English writer Norman Douglas in Old Calabria in the early twentieth century: “I was there in the golden hour that follows sunset, and again in the dim light of the dew-drenched morning; and it seemed to me that in this temple not erected by human hands resided a magic more natural and more sacred, than in the cloisters [of the Charterhouse of S. Stefano del Bosco] not far off.”

Serra San Bruno (VV)

Bernardino Poccetti - The Recruitment

The interior of the church of Maria SS. Assunta in Cielo houses an important painting by Bernardino Poccetti-The Annunciation-inspired by a canvas of the same subject kept in the church of SS. Annunziata in Florence.

Stylus (RC)

Ferdinandea

The Ferdinandea is an imposing building complex surrounded by the woods of the Serre Calabre and is located in the center of the Bosco di Stilo.

Ferdinandea, not the palace and/or hunting lodge of Ferdinand II of Bourbon, but over the centuries, which saw it active, it was a state-owned iron and steel-weapons plant, with an attached “workers’ citadel” and administrative offices. This guise of it certainly does not diminish its charm and importance.

The factory represented between the late 1700s and 1865, alongside Mongiana, the most important and innovative industrial intervention involving Calabrian steelmaking. Both were working-class citadels, military colonies and industrial apparatuses that operated and activated a significant induced activity in civil society as well.

Work on the Ferdinandea was begun by the Bourbons in the late 1700s. The purpose was to build in the mountains of Stilo a large foundry for large-caliber cannons, which would support the Mongiana foundry in war production.

The work, which was suspended several times, was completed in 1841, during the reign of Ferdinand II, to whom the foundry was dedicated. The large factory occupied an area of about 15,000 square meters, and was distributed in two separate buildings. The first, set in a horseshoe shape, with an inner court, housed the administrative residence, with offices, troop quarters, prisons, church, etc. The second, of which only two buildings remain, out of the four that originally existed, constituted in central body of the steel plant.

After the Unification of Italy, the Mongiana-Ferdinandea-Pazzano steel plant passed into private hands.

It was purchased by Achille Fazzari, a controversial figure of the Italian Risorgimento, who immediately began to resume the fusion campaigns convinced that he could “lift the fortunes of the population of the Convicini villages.” Unfortunately, his expectations were not long in coming up against bitter reality.

The government, which had already decreed the death of the Calabrian iron and steel industry by selling him the plants, caused him to miss public orders, and Fazzari, in order not to risk bankruptcy, was soon forced to close, and this time for good, his industries. He reconverted the Ferdinandea’s productions and elected it as his mountain residence, in which he hosted numerous personalities of the time, including the writer Matilde Serao.

The only “industrial” vocations, implemented, at Ferdinandea and in the Bosco di Stilo, were and still are those related to the exploitation of wood from the forests and the bottling of water from the Mangiatorella spring, initiated by Fazzari himself.

The Ferdinandea’s vast building heritage still resists abandonment and the ravages of time.

In the inner courtyard of the palace, there are relics from the Bourbon period: a cast-iron aedicule surmounted by a cannonball engraved with a dedication to King Ferdinand and a granite bust of the King. Both came from Mongiana brought to Ferdinandea by Fazzari. In the courtyard, softened by a small pond surrounded by a cast-iron balustrade, the artistic granite fountain is gone, disassembled and taken who knows where by the owners of the time. Also gone from the Ferdinandea are the artifacts kept in a small museum. The small church, now bare, retains something of its ancient furnishings.

Interesting is the monumental staircase of the “provinces,” which provides access to the upper floors of the palace, on the sides of which are drawn the coats of arms of all the Italian provinces of the time. From Ferdinandea, penetrating into the woods, one reaches, after about a kilometer, the large artificial reservoir Lake Giulia, built for the Marmarico power plant.

Pizzo Calabro (VV)

Murat Castle

The history of Pizzo Castle is linked to the death of Joachim Murat, King of Naples, a valiant, fearless man who sought victory and the reconquest of his kingdom in Pizzo and instead found death there.

Inside the manor a historical reconstruction reproduces the last days of Joachim Murat’s life, depicting the different moments of the imprisonment of the King and his men: ‘inside the cells, in the semi-subterranean rooms, their imprisonment is reproduced; on the second floor the scene of the summary trial against Murat is represented; in the cell where the King spent the last moments of his life and where he wrote his farewell letter to his wife Carolina and his four children, also on the second floor, the scene of the King’s confession with Canon Masdea is reproduced.

To visit Pizzo Castle is to relive firsthand the historical events that marked the destiny of a people.